Text and Context: Objects of Study in Critical Race Theory, African American Literature, and Racialized Bodies

Trying to write about and narrow the application of Critical Race Theory (CRT) to African American Literature has been simultaneously frustrating and illuminating. It’s frustrating because Critical Race Theory, by the very nature of a theory that seeks to invalidate stereotypes and labels, resists a one-size-fits-all application of its principles even within the same discipline. It has been illuminating because in trying to apply CRT to African American literature, I have encountered new ways to approach the study of African American literature, the law, and CRT. Thus, the fluidity and flexibility of CRT and even the various ways to approach the study of African American literature makes simple, clear-cut answers to this week’s questions impossible. Therefore, I can only address how I am going to attempt the study of CRT and African American literature and the objects of study particular to my approach. Much of my insight was gained through an interview with Dr. Delores B. Phillips (Old Dominion University, Postcolonial Theory and Literature).

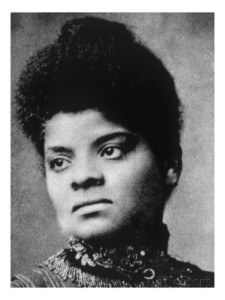

Anthony Ryan Hatch, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Georgia State University, Cultural Studies Critical Race Theory and Some Reflections on Methods (Hatch). Hatch includes the study of the social construction of race and the racism as essential to the tenets of CRT. Not explicitly mentioned in Hatch’s article is the role of the law in codifying and reifying social constructs of race and its influence on the administration of social systems throughout history. Instead, he focuses on the historical approach to understanding race and racism by emphasizing the importance of writers and activists like Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, and W.E.B. Du Bois and objects of study. Hatch also recognizes that this historical approach is intertwined with contemporary objects of study such as colorblind racism (Hatch) as the historical approach provides a foundation and understanding of the social construction of race from the 1700s through today (Hatch).

The difficulty with Hatch’s assessment of “race and racism” as the objects of study is that those terms on their own are ambiguous without the social context and cultural implications and materials that create their meaning. How do you study racism? Via interviews, surveys, observations? Hatch writes about core themes of CRT. It is these core themes, in my view, that provide some insight into potential objects of study: the American mythos of democracy and meritocracy, lived experiences, and colorblind racism, to name a few. Within these core themes, the approach that provides a more solid base of inquiry and study that involves one of the basic approaches to CRT: narrative – how these themes impact and influence race, racism, and identity in individuals and cultural groups. The collection and study of how people interact with American democracy, the observation of the impact of colorblind racism, etc. are all potential objects of study. However, it is Hatch’s emphasis on recognition of the historical foundation for modern CRT through the work of activists and writers like Douglass, Wells, and Du Bois that leads into my interest in African American literature. The study of their lives and their work is a connection and transition to the study of CRT as it applies to African American literature. It is not only their textual narratives that create the bridge, but the interactions with source of cultural, social and political power that serve as a catalyst for those narratives that apply CRT to African American literature.

The idea of studying literature through outside forces that shape a text is further developed in Maryemma Graham and Jerry W. Ward, Jr.’s study of African American literature and objects of study in the Introduction to the Cambridge History of African American Literature. Graham and Ward’s approach to studying African American literature is multi-faceted, beginning with the slave trade and slavery through contemporary America and its conflicting ideals of democracy and oppression (4). In this way, it is very similar to Hatch’s approach of using literary history as a foundation of CRT. It, however, is more specific as they state that “writers are not the sole shapers of literature” (4). Literature should be looked a via the historical forces that created the text, but also through the “roles of publishers, editors, academic critics, common readers, and mass media reviewers” that nurture, create, market, consume, and evaluate the texts (4). These are vital objects of study in the physical creation of the text.

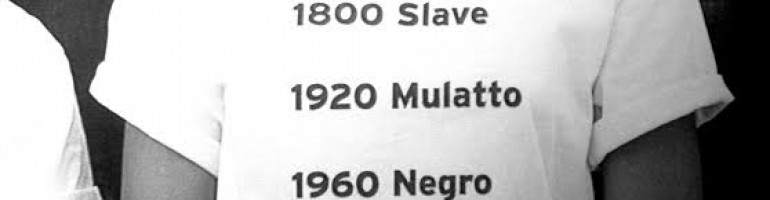

In my research of African American literature and CRT, I wish to pursue and in-depth study of the forces that shaped the text, the law, and the transaction between the text and the law and society. In particular, I am interested in how race and the law affect racialized bodies. Analyzing race through racialized bodies looks at race as “not merely a social category, but an embodied experience. This cluster brings together scholars who examine the ways that contemporary and historical notions of race, racial ideology and racial politics are manifested in how the “body” is represented, inhabited and regulated” (Blair). How are racialized bodies manifested in African American literature? How are racialized bodies manifested in culture and society? What is the transaction between bodies racialized by the law in society and culture and African American literature? How do people create counternarratives to resist racialized efforts to define and control their bodies?

During my October 10, 2014 interview with Dr. Phillips, we discussed critical race theory, African American cultural studies, African American literature, and racialized bodies. The interview helped narrow my approach to African American literature and focused my use of CRT analysis. For example, we discussed the increased exposure of police brutality and violence. When looked at through CRT, the focus is on how power and law reinforce power structures through violence against black bodies while still predominantly privileging white bodies in similar situations. This was clearly seen in last week’s #pumpkinfest where white college students at Keene College in New Hampshire participated in the annual pumpkin festival by rioting, destroying property, fighting each other, and terrorizing locals. Not only did the rioters taunt officers into using heavy duty militarized equipment, the police response was negligible compared to the police response to civil disobedience protesting the killing of an unarmed black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri. The internet did not take long to notice the discrepancy between how the police and the media treated the two events. Twitter was alight with satire and disdain for the way the drunk, belligerent white rioters were treated versus the way African American peacefully protesting a murder were treated. The difference is obvious — African American bodies are racialized and must negotiate state sanctioned violence in ways that white bodies do not.

One of these things is not like the other — the difference between how the police, media, and society view African American protesters and white rioters.

While CRT would focus on the interaction of law and race, a look a racialized bodies would analyze how the public violence against black bodies engaging in civil disobedience further stigmatizes black bodies and black anger as thuggish, dangerous, and in need of severe control. White bodies on the other hand, are sometimes “unruly,” but rarely dangerous. This analysis transfers to African American texts even when the law is not overtly present – how do racialized bodies move through the

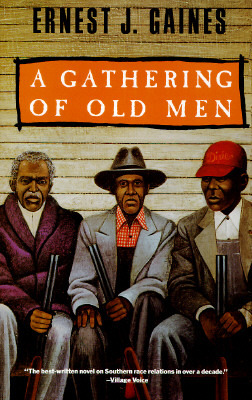

world and negotiate violence and outsider status even as citizens of their own community and nation? For example, in what I think will be one of my seminal texts, “A Gathering of Old Men” by Ernest Gaines, an African American man has killed a white man, Beau Boutan, in self-defense. The story centers not around justice, but against the threat of violence against African American men who dared to defend their bodies and their lives against violent social control. After discussing the direction of my research with Dr. Phillips we talked about centering my research around a literary text (for example, “A Gathering of Old Men”), pulling in a correlative cultural artifact (the television show “Cops”), and finishing with a legal case or legal topic that ties everything together. These things, the texts (and the forces that lead to their creation), the cultural artifacts, and the law will be my objects of study.

All of these perspective address the Major Questions of CRT and African American literature because it reinforces the fact that CRT is interdisciplinary, that there is no one way to address race and racism, and that objects of study are wide-ranging. Additionally, areas of study may splinter, combine, or be discarded without threatening the tenets of CRT because the tenets are fluid. I, however, have narrowed my research to the law as social control through the way it defines and creates race, racialization of black bodies, and the creation of texts as well as the text themselves.

Works Cited

Hatch, Anthony Ryan. Critical Race Theory. Ed. George Ritzer. N.p.: Blackwell Reference Online, 2007. PDF.

Phillips, Delores. Personal Interview. 14 October 2014.

Graham, Maryemma, and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. Introduction. “Cambridge History of African American Literature.” Cambridge University Press, 2010. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. PDF.