Theories and Epistemology

One of the most interesting and fulfilling facets of using Critical Race Theory to examine law and race in African American Literature is that the multidisciplinary approach inherent in CRT doesn’t require me to align my theories to narrow, artificial boundaries. There are two theories, however, that are central to, and intertwined with, CRT and African American literature: Narrative Theory, Legal Rhetoric (as a component of CRT), and New Historicism. I do not have preferred Objects of Study, as I am open to any text that allows for the reclaiming or recreation of personal and cultural identity. Thus, my personal objectives and professional objectives in Narrative Theory, Legal Rhetoric and Critical Race Theory, and New Historicism are inseparable. Additionally, these theories influence and are influenced by my social constructionism epistemological alignment.

Theories

Narrative:

Narrative theory “concerns itself with the structure of narrative – how events are constructed and through what point of view” (“Critical Approaches). The applicability of narrative theory to literature of any genre is obvious. I, however, want to go a step further in analyzing the language and structure of narrative to examine how law and race

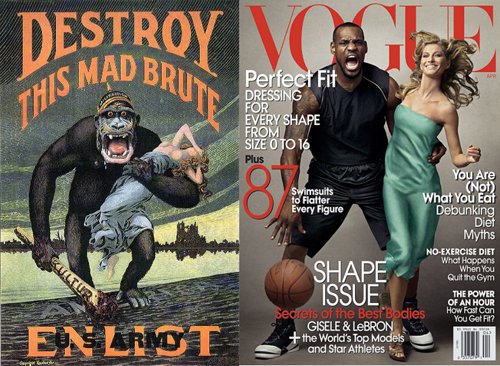

influence, among other things, literary characters, plot, and themes even when the narrative does not directly address issues of race. Race is an inescapable lived experience and Narrative Theory examines how socially and culturally African Americans are impacted by those experiences. For example, Frederick Douglass’s “Learning to Read and Write” is an important example of the how narrative and the creation of narrative is essential to understanding oneself as an African American. Frederick Douglass knew that he was a slave, but until he read the narrative of another slave in “The Columbian Orator” he did not know how to give voice or thought to his own condition. A narrative text enabled him to examine his own personal narrative and the voices, events, and structures that created who he was and how he thought about the world. Once he was exposed to this narrative, he was able to deconstruct it and begin to recreate it from his own point of view and perception of events. It becomes even more meta in that he was then able to create a written narrative from his own experience that deconstructed the narrative that others would try to create for him. This ability to create self-narratives in opposition to the damaging self-serving portrayal of African American masculinity, femininity, family, and history, among other things, is essential in establishing healthy self-perception and cultural identity.

Legal Rhetoric and Critical Race Theory:

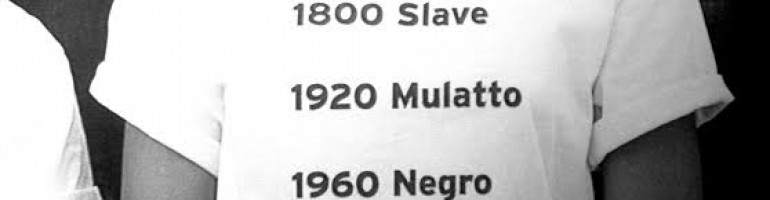

Narrative Theory, Legal Rhetoric, and Critical Race theory converge and is where my theoretical interests are most clearly reflected. Critical Race Theory focuses on the explicit and implicit interaction between power, race, and the law. Although there are many ways to engage with CRT, I am most interested in how legal rhetoric creates both personal and cultural identity and how the law and African Americans reinforce and/or resist the narrative created by those in power. As Haney Lopez states, the law is not a monolithic entity (114), but a system of interdependent mechanisms by which legal rules, social taboos and expectations, and “legal actors” engage in a system of racial definition and separation. How these racial definitions are redefined or reinforced in African American literature and how African American authors and readers create identity in opposition to the legal rhetoric that creates identity and the laws that reinforce racialization is the thrust of my inquiry.

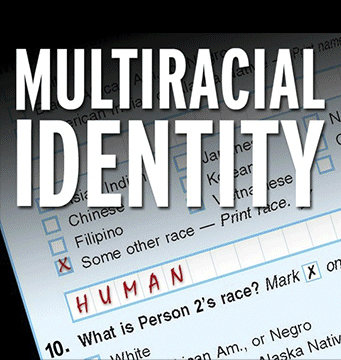

The dominant narratives and legal personas created by the law and legal rhetoric provide no real sense of authentic identification for African Americans. Examining African  American literature through a CRT lens limns the previously unacknowledged counternarratives and spaces that reshape and reclaim personal and cultural identity through resistance to legal definitions of race. The “mixed-race” movement in which people refused to acquiesce to the black/white binary established by the legal system resulted in an expansion of racial categories on the U.S. Census and other legal documents is one example of this resistance. Furthermore, this lens also exposes the ways that narratives and lack of personal or cultural resistance against them foster cultural and personal anxiety. Thus, personal and professional interests in how language creates identity drive this theoretical approach to my study.

American literature through a CRT lens limns the previously unacknowledged counternarratives and spaces that reshape and reclaim personal and cultural identity through resistance to legal definitions of race. The “mixed-race” movement in which people refused to acquiesce to the black/white binary established by the legal system resulted in an expansion of racial categories on the U.S. Census and other legal documents is one example of this resistance. Furthermore, this lens also exposes the ways that narratives and lack of personal or cultural resistance against them foster cultural and personal anxiety. Thus, personal and professional interests in how language creates identity drive this theoretical approach to my study.

New Historicism:

New Historicism “reflects a concern with the period in which a text is produced and/or read” (“Critical Approaches”). It also ties the texts to a broader range of ideas such as biography, cultural studies, the self, and literature as cultural texts. The necessity of using a New Historicism lens is evident given the reliance on how both Narrative and CRT and Legal Rhetoric are so closely tied with historical categories of race and examinations of identity and classification over time.

Epistemology

Social constructionism:

Zina O’Leary describes “social constructionism” as a “theory of knowledge that emphasizes that the world is constructed by human beings as they interact and engage in interpretation” (7). Social construction helps us understand and get our bearings about race, the law, language, and our place in the world. Some things we know only because we experience them and some things we know because we are given the language to relay our personal experience. All of that can only be understood or interpreted in light of the social constructs that give them context. However we define knowledge, it’s always bounded by the culture we live in. Thus, for me, knowledge and truth is based on lived experience and human interactions with the law and the social boundaries in which we exist.

Works Cited

“Critical Approaches to Literature.” Critical Approaches to Literature. Purdue University, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

Haney Lopez, Ian F. “White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race.” White by Law. New York: NYU Press, First Ed. 1996, 111-153.

O’Leary, Zina. “Taking a Leap into the Research World.” The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project. Chapter 1, 1-17.SAGE Publishing. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

.