Objects of Study & Critical Race Theory

Anthony Ryan Hatch, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Georgia State University, writes that Critical Race Theory is comprised of a larger body of thought than simply an offshoot of Critical Legal Studies in the 1970s and 1980 that examines how race and racism are created and perpetuated by the law (Hatch). Hatch states that while it may not have had a formal name, the work of writers and activists like Frederick Douglass, Ida Well-Barnett, and W.E.B. DuBois established the foundation upon which modern Critical Race Theory “interrogate[s] the discourses, ideologies, and social structures that produce and maintain conditions of racial injustice” (Hatch). Hatch describes the framework of this historical and contemporary movement against racism as “intellectual activism” (Hatch).

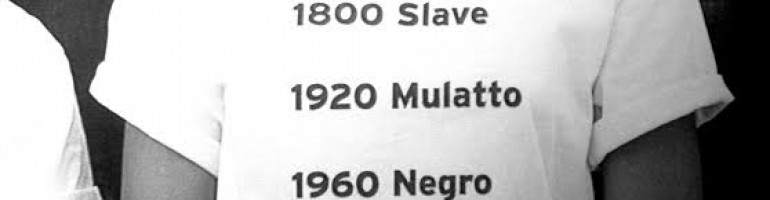

Hatch states that there are core themes that unite this wide-ranging body of work. The first core theme he addresses are the objects of study, race and racism. Using the historical framework, Hatch states that since the seventeenth-century, the social construction of race and the racism that accompanies it are essential to the administration of social systems, the rise of capitalism, and science and medicine from the 1700s through today (Hatch). His nod to contemporary approaches to Critical Race Theory includes institutionalized racism as coming under the umbrella of the race and racism objects of study.

Although I had never considered the historical perspective of activists and anti-racist work as part of Critical Race Theory, I can see how Hatch and other scholars connect a historical lens to contemporary discourses on race and racism. Additionally, I do not disagree with Hatch’s assessment of race and racism as objects, of study, but I think his statement is too vague. What does it mean to study race and racism? The answer is found in Hatch’s discussion of additional core themes of critical race study. Although he creates them as individual themes, they provide greater context and understanding of what studying race and racism entails – their objects of study.

The additional core themes are lived experiences, an interdisciplinary approach, a variety of methodologies, and science. Hatch also writes of American mythos of democracy and meritocracy, the emergence of colorblind racism, and contemporary proposals to undo systemic racism. The potential focus of objects of study under these core themes is vast. For example, as discussed in prior papers, lived experiences and narratives/story telling are essential to modern critical race theory that seeks to give voice to marginalized peoples. An object of study from an interdisciplinary approach would be determined by the discipline. If utilizing CRT in the study of anthropology, one could examine bones and teeth to determine health and other physical characteristics of minority peoples in a certain period of time or geographic location and provide information about social status or even genetics. A modern approach to CRT would use the law and legal institutions (as discussed in prior posts) but also, social media such as dating sites or (Online Dating, An Uneven Playing Field for Black Women) even tumblr (Microaggressions, Power, Privilege and Everyday Life) for information about race and racism in modern institutions.

In my view, any limits on objects of study in Critical Race Theory would be artificial given that CRT is almost limitless in its interdisciplinary, social, and cultural approach to examining the broad category of race and racism.

Works Cited

Hatch, Anthony Ryan. Critical Race Theory. Ed. George Ritzer. n.p.: Blackwell Reference Online, 2007. PDF.

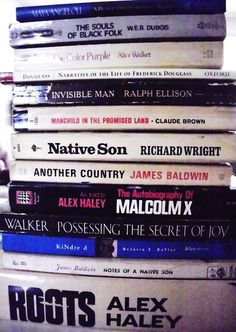

African American Literature — A different approach to Objects of Study

Because I am interested in Critical Race Theory as a lens through which to approach African American literature, I looked at objects of study for literary studies, knowing that there had to be more than just “look at the books.” Maryemma Graham and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. address one way to approach the study of African American literature and objects of study in the Introduction to the Cambridge History of African American Literature. Graham and Ward state that literary historians approach the study of literature through “shaping stories about texts and contexts (3). They site Mario J. Valdes and Linda Hutcheon’s Rethinking Literary History: A Dialog on Theory (2002) as placing a focus not just on the writing produced, but the forces that helped create the writing and the literary history (3).

Although a literary historicist approach to African American literature looks at African American literature as it is:

- Related to the slave trade and the institution of slavery in the United States.

- The creation of African American identity through the amalgamation of various African ethnic groups.

- Contact between African, native, and European groups that created new forms of oratory and expression.

- The struggle for freedom, education, and literacy.

- The social dynamics of race.

- American democracy and its ideologies. (4)

While I think these points are important in understanding the creation of African American identity, I will need to read further to see how several of these points influenced

African American texts. I am more intrigued by their statement that “writers are not the sole shapers of literature” (4). They state that the “roles of publishers, editors, academic critics, common readers, and mass media reviewers” shape texts and tastes. To me, these should be considered objects of study when it comes to analyzing and interpreting African American literature.

For example, I’m thinking of the limited range of exposure African American authors get in mainstream literary recognition. Everything from African American-centric novels being segregated from mainstream (read “White”) novels in bookstores and libraries, to white female authors achieving recognition for writing about African American women’s experiences while African American female authors struggle for recognition. These forces can’t help but shape what African American authors write and what African American readers read, and are just as important to studying African American literature as the actual texts themselves.

While this article doesn’t directly address the objects of study I had intended to investigate (how race and racism is interrogated in African American literature), it opens up ways to examine how race and racism in the production of African American literature influences African American texts.

Works Cited

Graham, Maryemma, and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. Introduction. “Cambridge History of African American Literature.” Cambridge University Press, 2010. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. PDF.