Being a scholar of ???

This weekend I will place myself in the midst of an ongoing debate in American society. I will stand in front of City Hall and recite the names of African American men, women, and children who were victims of police brutality and excessive force. In addition to being murdered, their stories and identities were high-jacked by the police to rationalize their brutal deaths. The media was complicit in framing these men, women, and children as welfare queens, thugs, and wayward products of a morally bankrupt and crime-ridden culture. It is a tactic as old as the story of the first African to survive the Middle Passage. Dehumanize him and you can justify and blame him for any harm he endures.

As I stand in the winter cold, I will be the embodiment of Critical Race Theory as I push back against racism, power, and the law. I will challenge the legal rhetoric and language used to dehumanize the victims and assert a personal and cultural identity in an era that claims not to see my skin color at the same time as it erects and fortifies institutional, structural, and systemic racism.

One of Zora Neale Hurston’s most famous quotes interpreted literally with black print on a white background.

Being a Scholar of Race, more specifically Critical Race Theory, Legal Rhetoric, and Cultural Studies in the formation of personal and cultural identity is much more than an academic endeavor, it is personal. As Zora Neale Hurston stated, “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp, white background.” Critical Race Theory’s origins in the social justice movements of the 1980s appeal to my sense of justice, my conflicting feelings about law, and the use of counter-narratives that are the basis of Critical Race Theory to rewrite ourselves back into history and push back against the structures that seek to define and contain us. In this aspect, I see myself engaging in the social justice arm of Critical Race Theory through protest and on the street activism. The early pioneers of the movement were willing to sacrifice their careers, often engaging in protests alongside their students and members of marginalized communities. The social activism aspect of Critical Race Theory has evolved to include contemporary concerns such as environmental justice and prisoner’s rights. While these areas impact African American communities, I see myself focusing my social activism on abuse of power in the courts and police on the streets.

This semester has taught me that perhaps my role in Critical Race Theory and my chosen subdisciplines lies outside of the academy. I don’t think the academic world of analyzing race and racism and writing papers is enough for me. I see myself contributing by getting out of academia, at least outside of research, conferences, and the pedantic ego-stroking and infighting. One possible area I see myself pursuing is getting back into law in the area of civil rights litigation. Maybe I’ll remain myself in the classroom where the impact is on the individual level. My most rewarding classes are the ones in which I see students evolve from close-minded superficial thinkers to critical consumers of the mass media who can evaluate social justice issues and the intersectionality of race, class, and gender in their own lives and the lives of others. One thing that CRT has taught me is that you can’t topple the top without first destabilizing the base. In regard to race and other social justice issues, I am destabilizing the base not by telling them what to think, but by teaching them how to think.

Should I choose to stay in academia, I find the modern arm of Critical Race Theory that focuses on the contemporary issues of race, law, and power that were not present when the discipline was first conceived ripe for research and examination. My approach to CRT maintains the “old school” focus on social justice and combines it with the

Microaggression percentages with frequency level greater than “a little/rarely” broken down by race.

contemporary interest in how race and microaggressions shape personal and cultural identity in the law. For example, I was recently discussing African American anger and stereotypes of the Angry Black Woman and the Dangerous Black Man. As I wrote in Paper #2, both of these stereotypes are used in an attempt to derail discussion about the circumstances that lead to the real, or perceived anger. Often, it’s not even the overt racism that results in the frustration and anger (ironically, when non-people of color demonstrate anger, it’s often called righteous anger, passion, or even patriotism, depending on the circumstances), but the multitude of microaggressions over a day, a year, a lifetime that result in the harsh tone or outburst when someone asks to touch your hair (this is not a zoo), states that you are articulate (unspoken: for a black person), asks “What are you?” (I’m a who, not a what), questions your credentials (do I need to pin my resume and recommendations to my chest?), or gives you a backhanded compliment (as in the recent kerfluffel with the New York Times columnist who called Shondra Rhimes, an accomplished and successful producer of hit televisions shows, an Angry Black Woman and expected it to be perceived as a compliment) that often go unaddressed by social justice and anti-racist activists.Not addressed in Paper #2 is the fear of being accused of being an Angry Black Woman or Dangerous Black Man. This anxiety often deters African Americans from asserting a genuine or authentic voice. The Angry Black Woman and Dangerous Black Man narratives or a silencing tactic designed to quell dissent and individuality. Not only have I seen this in numerous articles and studies that address these stereotypes, but I have subjected myself to the self-doubt that occurs when I want to speak up about an issue. Although written over a century ago, W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Souls of Black Folks” accurately describes this internal/external dialogue as “double consciousness”:

Not addressed in Paper #2 is the fear of being accused of being an Angry Black Woman or Dangerous Black Man. This anxiety often deters African Americans from asserting a genuine or authentic voice. The Angry Black Woman and Dangerous Black Man narratives or a silencing tactic designed to quell dissent and individuality. Not only have I seen this in numerous articles and studies that address these stereotypes, but I have subjected myself to the self-doubt that occurs when I want to speak up about an issue. Although written over a century ago, W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Souls of Black Folks” accurately describes this internal/external dialogue as “double consciousness”:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He does not wish to Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He wouldn’t bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.

As a side note, I am fully aware of the difficulties African Americans face in academia and realize that being an African American woman in higher education is an uphill battle. I find that asserting myself in meetings or even in the classroom offends people in a way that would not occur with a white male. If you are not African American and have never experienced this, you are just going to have to trust me on this. So part of my dilemma is whether or not I want to engage in the liberal colorblind racism that I will encounter in academia or go to a more welcoming environment. For example, museums like the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh had an exhibit entitled RACE: Are We So Different? The prospect of consulting with museums, businesses seeking to establish real, effective diversity initiatives, or working for non-profits such as the Equal Justice Initiative is appealing.

But back to race, law, and power — overt racism, microaggressions, and other stereotypes find their way into the legal system. Mario L. Barnes, Professor of Law at University of California, Irvine and Co-Director of the Center for Law, Equality, and Race compiled information about black women’s interactions with the criminal justice system and found that “social and legal constructions of black women’s identities” resulted in stereotypes and prejudices made their race hypervisible to the exclusion of facts, or opaque observers in the courts rather than participants (945).

Barnes’s study established how courts use racialized social codes and stereotypes to create a negative black female identity that undermines not only individuality of the

Do racialized stereotypes used to get television ratings impact minorities in court? You bet they do.

women, but the court proceedings themselves (950). Not only are personal narratives used to demonstrate the dehumanizing racism of the justice system, but dehumanizing narratives are created by the justice system in order to justify racially loaded determinations from racially neutral facts (967).

In addition to creating a false identity, the hypervisibility of racially coded traits serve to diminish social status (969). Barnes provides an example of welfare status as in example of an identity trait being imbued with racial overtones (970). In his example, welfare is often used as a sign of low status and thus, low character (970). Barnes claims that welfare is also conflated with race and culpability (970), thus creating an image based on traits regardless of any real culpability. African American women are often treated as guilty because their race is hypervisible to a court that imbues their dark skin with legal prejudices and biases. Barnes’ notes that when black women are on trial, their morality is also on trial regardless of any direct link to the case before the court. The number of sex partners, the number of children, and references to morality are all elements of hypervisibility that affect the attitudes of the triers of fact, but also play into the stereotype of the wanton, sexually reckless black woman (974). While this determination is not a legal one, it is a social construction that is destructive both in and outside of the court room.

Barnes’s research provides a way to approach Critical Race Theory from a perspective that makes it less of an academic thought experiment and more of a practical way to effect change. One way I see myself contributing to and extending Barnes’s research is through a Cultural Studies approach to Critical Race Theory. Although Barnes’s research focuses on the law and stereotypes, those narratives are coded and reinforced in the law and in American culture. As stated in PAB #2, Imani Perry’s work would provide an entry way for discussing cultural narratives that impact the law. In her article Cultural Studies Critical Race Theory and Some Reflections on Methods (2005), Perry argues for examining the narrative created by “social practices and forms of consumption (television, church, film, games) (917)” and evaluating those cultural artifacts “as they relate to the structural power of law, and the underlying ideologies of constitutional and private law” (917). For example, rather than disdain the “low brow” appeal of pop culture such “paternity test shows” that create and reinforce stereotypes about race (917), Perry argues that such artifacts of cultural production should be read as a series of interdependent texts that communicate values that influence, and are influenced by, law (917).

In particular, my Cultural Studies Objects of Study would include, among other things, police reality TV shows, news reports, print media, commercials, blogs, press releases, and police and eyewitness testimony. Through an analysis of these texts, it is possible to examine law and culture as social control through the way they define and create race and the racialization of black bodies. During my October 10, 2014 interview with Dr. Phillips, we discussed critical race theory, African American cultural studies, African American literature, and racialized bodies. The interview helped narrow my approach to African American literature and focused my use of CRT analysis. For example, we discussed the increased exposure of police brutality and violence. When looked at through CRT, the focus is on how power and law reinforce power structures through violence against black bodies while still predominantly privileging white bodies in similar situations. This was clearly seen in #pumpkinfest where white college students at Keene College in New Hampshire participated in the annual pumpkin festival by rioting, destroying property, fighting each other, and terrorizing locals. Not only did the rioters taunt officers into using heavy duty militarized equipment, the police response was negligible compared to the police response to civil disobedience protesting the killing of an unarmed black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri . The internet did not take long to notice the discrepancy between how the police and the media treated the two events. Similar disproportionate response by police officers have been noted in how they seek to quell civil disobedience in the wake of the death of Eric Garner following an banned chokehold by a white police officer.

Another example of law, language, and narrative in creating racialized body is in Darren Wilson’s Grand Jury testimony. Aside from the other legal irregularities, Wilson characterized Michael Brown as a “demon” and expressed fear at his size. – Michael Brown was no longer an 18-year old, he was a beast. As Wilson claimed,

Michael Brown was a dangerous Black man. As a litigator I know how language and stories are essential to creating persuasive arguments. How lawyers construct narratives is similar to the way authors, producers, and other storytellers construct narratives. As an avid reader and literature professor, I see how texts are living and how society is reflected in the texts and how texts are reflected in society – they are a mirror of who we are. How Wilson described Brown is how society sees African American men. I want to examine real trial testimony, police reports, and press releases. Additionally, I want to examine African American literature that contains trials, police encounters, and any other interactions with power, law, and racism beginning with Richard Wright’s “Native Son,” a powerful and scathing protest novel that addresses race, racism, law, and the narratives we create and the narratives we allow others to create for us. It is one of the most influential African American protest novels.

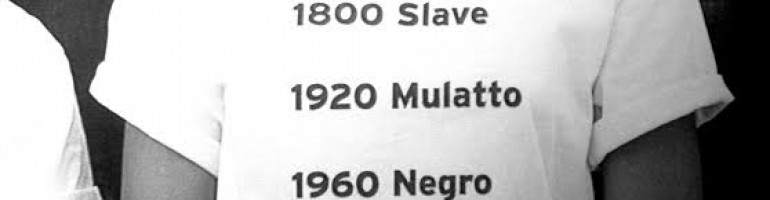

Since literature and cultural artifacts, such as reality television, bestseller lists, and press conferences, are not created in a vacuum, a New Historicism approach which “reflects a concern with the period in which a text is produced and/or read” (“Critical Approaches”), would be a secondary lens through which to view these texts. The necessity of using a New Historicism lens is evident given the reliance on how both Narrative and CRT and Legal Rhetoric are so closely tied with historical categories of race and examinations of identity and classification over time and how those identities are mirrored and reinforced in culture. New Historicism would also be useful in examining how the law in effect at the time implicitly and explicitly influenced not just the creation of the text, but the content as well and how culture influenced the law (i.e. Barnes’s study about the legal impact of cultural stereotypes in the courtroom).

As I stated in Paper #5, Narrative Theory, Legal Rhetoric, and Critical Race theory converge and is where my theoretical interests are most clearly reflected. Critical Race Theory focuses on the explicit and implicit interaction between power, race, and the law. Although there are many ways to engage with CRT, I am most interested in how legal rhetoric creates both personal and cultural identity and how the law and African Americans reinforce and/or resist the narrative created by those in power. As Haney Lopez states, the law is not a monolithic entity (114), but a system of interdependent mechanisms by which legal rules, social taboos and expectations, and “legal actors” engage in a system of racial definition and separation. How these racial definitions are redefined or reinforced in African American literature and Cultural Studies how African American authors and readers create and resist narration and navigate the strictures and limits imposed by law will probably be a focal point of my research.

The dominant narratives and legal personas created by the law and legal rhetoric provide no real sense of authentic identification for African Americans. Examining African American literature through a CRT lens limns the previously unacknowledged counternarratives and spaces that reshape and reclaim personal and cultural identity through resistance to legal definitions of race.

My epistemology naturally emerges from my objects of study and my theories. While qualitative and quantitative research is essential to gathering knowledge, social constructionism most aptly describes what how I determine truth and evidence. As I stated in Paper #5, “social constructionism” is a “theory of knowledge that emphasizes that the world is constructed by human beings as they interact and engage in interpretation” (O’Leary). Social construction helps us understand and get our bearings about race, the law, language, and our place in the world. Some things we know only because we experience them and some things we know because we are given the language to relay our personal experience. All of that can only be understood or interpreted in light of the social constructs that give them context. However we define knowledge, it’s always bounded by the culture we live in. Thus, for me, knowledge and truth is based on lived experience and human interactions with the law and the social boundaries in which we exist.

As stated at the beginning of this essay, I’m not sure where all of this leaves me. I recognize the value in academic research, in fact my knowledge of the impact of the law on race and racism and my ability to take part in protests and demonstrations is because someone has already done research on these issues. However, at this time, I think my best use of the academy is to apply the research and studies created by other scholars in the field to make my work in the streets, the classroom, the non-profit, or the courtroom more effective.

Works Cited

Barnes, Mario L. “Black Women’s Stories and the Criminal Law: Restating the Power of Narrative.” 39 U. C. Davis L. Rev. (2005 -2006): 941-90. Web. 05 Sept. 2014.

“Critical Approaches to Literature.” Critical Approaches to Literature. Purdue University, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

Haney Lopez, Ian F. “White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race.” White by Law. New York: NYU Press, First Ed. 1996, 111-153.

O’Leary, Zina. “Taking a Leap into the Research World.” The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project. Chapter 1, 1-17.SAGE Publishing. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

Perry, Imani. “Cultural Studies, Critical Race Theory and Some Reflection on Methods.” 50 Villanova Law Review 4 (2005): 915-24. Law and Society Commons. Web. 20 Sept. 2014.