Looking Back, Moving Forward

Richard Delgado ‘s “Liberal McCarthyism and the Origins of Critical Race Theory” (2009) and Kimberle Williams Crenshaw’s , “Twenty Years of Critical Race Theory Looking Back to Move Forward” (2009) trace the development of Critical Race Theory (CRT) from the backlash in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s against progressive professors advocating for social reform to what Williams calls the “institutional and discursive struggles over the scope of race and racism” (1259)on the campus of Harvard in the 1980’s. These birth stories define the impetus of the movement as a response to institutional inertia and de facto segregation and the loci, the American higher education system.

Delgado asserts that “liberal McCarthyism” within the higher education system resulted in the ejection of civil rights activists from the academy. Ironically, it was in response to liberal pressure to depoliticize campuses and prevent radical professors from influencing the influx of African American students making their way into higher education for the first time as a result of Brown v. Board of Education.

David Trubek was hired at Yale in the late 1960’s, but was denied tenure for supporting student activism against Yale’s “let the courts do their work” mentality. Trubek’s political views resulted in an unstable academic career, during which he mentored and advised Kimberlie Williams Crenshaw, who became one of the leading members of CRT. Her dissertation is a doctrinal CRT document (1536). He also sponsored the participation of Crenshaw and a group of minority professors at the “New Developments in Minority Scholarship” panel, recognized as the foundation of CRT (1536).

Another Yale professor, Richard Able also drew the ire of the administration. His critiques of law, government, and of Yale’s own resistance to social reform resulted in his dismissal (1537). Like Trubek, Able’s most important contribution to CRT occurred when he organized the “New Developments in Minority Scholarship” panel (1537).

Staughton Lynd, also a Yale professor, took his activism beyond the classroom to speak at rallies and participate in protests (1539). Even after his dismissal, he continued

to write and influence CRT, as his material-determinist view of the intersection of race and history influenced Derrick Bell Brown v Board and Interest Convergence (1539).

Delgado’s analysis of Trubek, Abel, and Lynd’s influence on CRT neatly intersects with Crenshaw’s discussion of the frustrations and activism of African American law students at Harvard Law School. In 1982, Harvard Law’s Black Law Student Association confronted their concerns over the lack of minority professors (1264). Derrick Bell, a well-respected African American law professor, had left earlier that year in frustration over Harvard’s hiring policies and refusal to review hiring practices that eliminated qualified professors of color (1265). With Bell’s departure went all courses that dealt with law and social justice, a particular concern to minority students who were in the first wave of law students to benefit from Brown v. Board of Education. Not only did the dean minimize their concerns, but his response was tinged with condescension and more than a bit of racial tone-deafness. It was clear to Crenshaw and other Harvard Law minority students “whose legal problems would be served by Harvard Law School and which interests were not” (1274).

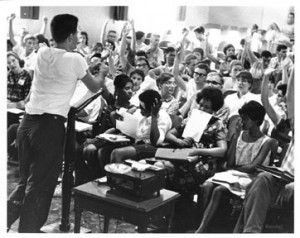

Derrick Bell walking with a group of Harvard Law School Students after taking his voluntary leave of absence.

In 1989, Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, David Trubek, and twenty-one others developed a “New Developments in Minority Scholarship” panel, organized in part by Richard Abel, at a CLS conference in Madison, Wisconsin. Not only did the documents produced for this panel create the foundation for CRT, but as Crenshaw states, “[they] were able to link [their] projects together within an emerging ideological frame. The project thus grew into its name: Critical Race Theory” (1300).

CRT embraces methodologies and adapts theories from other disciplines to examine the roots and exercise of power on individuals and institutions. CRT not only pervades legal study, but is also cross-disciplinary tool used in “education, psychology, cultural studies, political science, and even philosophy” (1256). Unlike other areas of study, such as Game Studies discussed last week, CRT does not derive its principles based on exclusion or by drawing narrow boundaries. In fact, such practices would be antithetical to its origins.

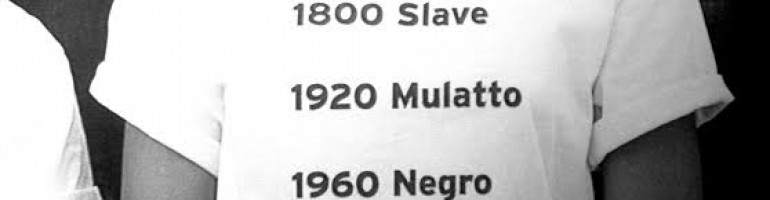

One of the questions I have about CRT is how it has adapted to 21st century ideas about race and the expansion of racial and ethnic categories. In my own life I have wrestled with racial identification, often from the outside as others seek to label my race and ethnicity. Upon reflection and through my study of CRT, I realize that while most of it has been well-meaning, there is always a hierarchy to labeling and people express a bizarre satisfaction in being able to peg what racial/ethnic group I claim. I am interested in how these dynamics are incorporated into the race/power dynamics of the legal system.

Finally, in researching the history of the CRT movement, I thought about ways to connect it to my interest in African American literature. I am particularly drawn to Native Son by Richard Wright and A Gathering of Old Men by Earnest Gaines and how African American men operate within and resist definitions of race and the power of the law.

Works Cited

Delgado, Richard. “Liberal McCarthyism and the Origins of Critical Race Theory.” Iowa Law Review 94 (2009): 1505-545. Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

Crenshaw, Kimberle Williams. “Twenty Years of Critical Race Theory.” Connecticut Law Review 43 (2011): 1253-352. Web. 10 Sept. 2014.

Recommended Reading

Crenshaw, Kimberlé, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Thomas Kendall, eds. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New York: New Press 1995. Print.

Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. 2nd ed. New York: New York UP, 2001. Print.

I learned so much from your first paper and the history of Critical Race Theory. We discussed just a few areas of CRT as part of my post-colonial literature class last term and with this awareness came my realization that I really knew nothing and needed to read so much more. Reading about the origins of CRT as part of the liberal wave on campuses, yet how it really demonstrated their “institutional inertia and de facto segregation” shows how important of a field this is in the academy. Tying together history drawing from subjects typically not associated with English Studies, like law, political science, etc… I agree that “race/power” dynamics seem to cross disciplines. Your comment about how people try to “label” within a hierarchy is interesting, especially as I look across the paper posts and see this in effect in so many discipline areas – whether it is by race, gender, origin – as in L2 or Native American…what is the satisfaction in naming? Great questions – I look forward to reading more on the subject in your posts.

Hi Carol, thanks for your comment. Labeling is definitely part of power dynamics. If you can label someone or something, you can then put them in relation to something else (race or power, for example). We see the difficulty with labeling, as you notes, in disciplines. Not having a label makes it awkward and people question your validity (English Studies), but chose the wrong or less powerful label and either end up being misidentified or marginalized. I’m interested in researching this further.

Wow Shana! I feel so silly in saying this, but I had no idea that institutions like Yale and Harvard were actively suppressing scholars like Trubek and Able, in a move to quell any unrest after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education. It makes sense that this is what happened in the era of Brown v. Board of Education, especially with the broad, retrospective view I can take on English Studies through this course, but I feel naïve in failing to connect the dots before. Bearing this in mind, I now question exactly how far behind the times higher education actually is; we have some of the most brilliant individuals in the world working in our institution (who have produced astounding scholarship and led incredible activism), and then we still have Dr. Henry Gates being arrested for entering his own home in 2009. It’s certainly “liberal McCarthyism,” as defined by Delgado, but where did it come from? I know you mentioned that Delgado argues it came from liberal forces within higher education trying to depoliticize the campuses after the Counterculture and Civil Rights movements of the sixties and seventies, but it makes me question: can we really refer to higher education as liberal then? Or, was that adjective liberal slapped on universities in the sixties and seventies by politicians like Nixon (and then Reagan, and then Bush) because of the civil disobedience taking place, with actually conservative, top-down commands being given from university administration offices? Perhaps this seems like a moot point, but when I read your paper, warning sirens went off in my head, because this liberal McCarthyism is antithetical to academic freedom. Your work makes me consider my own work on Native American literary studies right now, and completely legitimizes the concerns/arguments of the Native scholars I have been reading—particularly their unhappiness with there being very few Native scholars actually teaching Native work at universities. Very interesting! –Meredith P.

Meredith,

We see that liberal education is often a reaffirmation of the status quo when we look at how few women there are in positions of power in academia and how they are paid less, penalized more (maternity leave, etc.), and not as respected by admin and students. I think higher education is liberal to an extent — I think that the move toward education as a business model has reduced growth in that direction. If higher education is more about making money, that means making the students, who are now customers happy — which often translate into not challenging them to think critically because it’s hard. I think higher education, for all our talk of being liberal and wanting to educate students to think critically, has a stake in upholding the status quo. Therefore, its wasn’t the schools themselves that were liberal, but the students and a few forward thinking teachers.

I actually want to discuss Native American writers with you. I’m thinking of how it relates to my own work. I am focusing on African American Literature and thinking of coming at it from the perspective of belonging, yet not belonging. It’s almost as if African American and Native American Literatures has much in common with immigrant literature.