Liberal McCarthyism and the Creation of Critical Race Theory

In 2009, Richard Delgado, co-founder of Critical Race Theory and the current John J. Sparkman Chair of Law at University of Alabama, wrote “Liberal McCarthyism and the Origins of Critical Race Theory.” Delgado commemorates the origins of Critical Race Theory by explaining how seemingly unconnected forces were essential in the formation of the movement (1506). The recognition of origins, he claims, is necessary for any movement because it serves a “constitutive function” by “designating an official ideology, selecting a set of heroes, and avoiding the appearance of contingency and luck in explaining how the group came into existence” (1506). In short, birth stories for movements, like people, give a sense of stability, legitimacy, and even identity.

Derrick Bell’s powerful and groundbreaking Critical Race document “Brown v Board of Education and Interest Convergence” is credited with beginning the Critical Race Theory movement. However, Delgado makes clear that Bell’s bellwether article is the culmination of the actions and potentially career ending sacrifices made by educators David Trubek, Richard Abel, Staughton Lynd, and Anthony Platt in the years leading up to official recognition of Critical Race Theory.

Still reeling from protests, student activism, and unrest of the 1960s and 1970s, universities sought to return to an equilibrium that satisfied the status quo. What resulted was a national witch hunt that Delgado calls “liberal McCarthyism,” in which professors active in social justice and reform were fired, denied tenure, and blackballed from jobs in higher education. Rather than be cowed by ejection from the academy, Delgado describes their continued efforts on behalf of social reform by establishing connections, convening panels on race and law, writing articles, and mentoring students who were essential in forming that basis of what we know today as critical legal studies and critical race theory.

In gathering their stories, Delgado utilizes Staughton Lynd’s “history from below” approach and merges those histories into one overarching birth story, demonstrating the unified purpose, methodology, stability, and identity that created Critical Race Theory. Delgado recognizes that fragmentation and the absence of a clearly defined origin and ideology make it difficult for a movement to gather momentum and articulate goals. Borrowing from various disciplines there was a tacit understanding of mutual goals that enabled the movement to thrive in a time of instability.

English Studies is experiencing those difficulties today. Although, Critical Race Theory has had offshoots such as Critical Race Feminism and Critical Latino Theory, they are stronger because they share a common core and related goals. From what we have studied so far, English studies not only has disparate offshoots, but these offshoots resist acknowledging a common core and often cannot identify their own goals. This has made me recognize that in entering and engaging with my discipline, one of my goals should also be definition as a scholar within the discipline. This article has already contributed to my understanding of the discipline. In other words, roots give wings.

Questions:

- Although higher education was predominated by white men, I’d like to learn more about the “history from below” of women and minorities involved in the movement.

- Many of these men eventually returned to academia. I would like to know how they and others negotiated that return and their how they practice or implement Critical Race Theory in a so-called post-racial society.

Key Concepts/Terms

Interest Convergence: Social justice for African Americans is only possible when the needs of African Americans intersect with the needs of the White majority (Bell 523)

Critical Race Theory: “Radical legal movement that seeks to transform the relationship between race, racism, and power” (Delgado “Glossary of Terms”).

History from Below: That stories of the nameless, faceless people that shape history through their “invisible actions – rather than the traditional version emphasizing generals, kinds, and wars” (Delgado “Liberal McCarthyism” 1538).

Works Cited

Derrick A. Bell, Jr., Comment, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” 93 HARV. L. REV. 518 (1980)

Delgado, Richard and Jean Stefanic. “Glossary of Terms”. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York New York. Univ. Press 2nd Ed. (2012) 159

Delgado, Richard. “Liberal McCarthyism and the Origins of Critical Race Theory.” 94 Iowa Law Review (2009): 1505-545. Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

Critical Race Theory: Then and Now

Kimberlie Williams Crenshaw, who wrote one of the foundational texts of Critical Race Theory, “Race Reform Retrenchment,” looks back on the movement in her Connecticut Law Review article, “Twenty Years of Critical Race Theory Looking Back to Move Forward.” Crenshaw’s article discusses the differences and similarities of the Critical Race Theory’s beginnings and the challenges of a multi-disciplinary methodology and application along with opportunities and obstacles that developed in our “post-racial era.

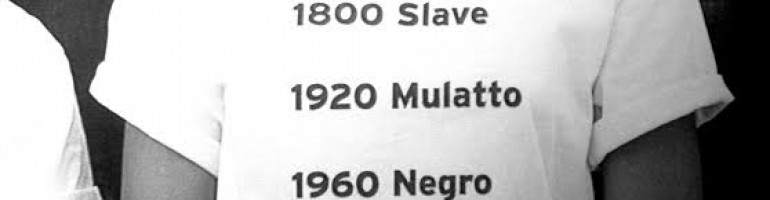

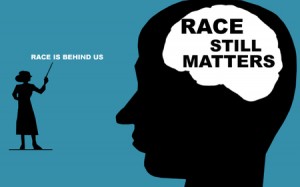

Crenshaw takes an encompassing look at the perceptual problem of Critical Race Theory among Conservatives and accusations of anti-Semitism that threatened the survival of the discipline (1311). Although for many, Barak Obama’s election seemed to indicate that the United States was ushering in a new era of equality and race reform, Crenshaw argues that “formal equality did little to disrupt ongoing patterns of institutional power and the reproduction of differential privileges and burdens across race” (1312). According to Crenshaw, reframing and broadening Critical Race Theory is vital in order to address the contemporary issues of race, law, and power that were not present when the discipline was first conceived (1313). She posits that Critical Race Theory must deal with seemingly benign colorblind racism and address what she calls “the Obama phenomenon,” that is, that with the election of an African American president, America needs to no longer concern itself with race. When in fact, his election presented a double-bind for African Americans. By claiming to not see race, colorblind racism ignores the structural and institutional racism that made Obama’s election not so much a victory, but a miracle. It serves to allow some well-meaning colorblind to be blind to the social, political, and other inequities still in existence and provide an excuse for racists to adhere to their notions of African American self-sabotage and missed opportunities for advancement.

Crenshaw’s analysis of critiques Obama’s reframing and often avoidance of discussions of race, has been a hindrance rather than a help to racial equality and social justice.

In fact, they have assisted not only the courts, but also the American people in drifting back to the harmful ideas about race and power that existed during Critical Race Theory’s early period. She also addresses a “drifting back” by claiming that Critical Race Theory is in danger of becoming too tied to the civil rights activism of the past rather than incorporating the various formats of twenty-first century activism and the more subtle ways that race and power collide. Rather than progress, Crenshaw writes, the post-racial world has been a series of regressions that establish the need for a Critical Race Theory that addresses post-racial discourses and moves the movement forward.

Crenshaw’s article not only encompasses the “post-racial” era, but addresses women in law and academia, and the necessity of an interdisciplinary approach to Critical Race Theory. I found this article valuable in answering questions about the progression of the movement and the incorporation and recognition of other voices within the movement. So many articles about race and law focus on black men. This article was helpful not only for its attention to women, but because it went in greater detail about CRT’s application to other areas of study. As I continue to develop my area of interest, the continued application of CRT to other areas was much needed guidance.

In terms of its application to English Studies, what was interesting about this article is that unlike its conception, CRT has become an accepted discipline within various academic departments. It is still a unifying force among LatCrit theorist, Critical Race Feminists, and others. The divergence of interests has only served to strengthen CRT over time rather than diminish it.

In the attached video, Crenshaw addresses pervasive structural inequality and how CRT can address it. It’s an interesting keynote address if you have time to watch it. I would be interested in your thoughts. I am working through thoughts about CRT and how/if I would apply it to my research interests, so I would appreciate any questions or comments you have about the post or the video.

Works Cited

Race, Reform, and Retrenchment: Transformation and Legitimation in Antidiscrimination Law, 101 Harvard Law Review 1331-87 (1988). Reprinted in Critical Legal

Thought: An American-German Debate (edited by Christian Joerges and David M. Trubek, Nomos, 1989